Land Values and Affordability

The relationship might not work the way you think

I want to get something off my chest: attempts to keep the price of urban land down are not necessarily good. Many people in local politics place a high priority on keeping land prices down. For example, the new Vancouver councillor who opposed a church building apartments on their own land:

Land values displace people. This will increase land values.

…and then used that same reason to vote against apartments at a major train station:

I’m worried that filtering will take too long, that land value increases will lead to displacement…

Vancouver’s planning staff share these concerns and try to keep land values down when changing zoning. For example, the recent multiplex policy was designed to avoid raising land values:

Land Prices Are Not Housing Prices

The main way people save on housing costs in cities is by using less land. For example, imagine the following uses on a 4000 sqft lot:

| Building | Land/Household |

|---|---|

| Single family home (small) | 4000 sqft |

| Duplex | 2000 sqft |

| 5-unit apartment/condo building | 800 sqft |

It is generally much cheaper to buy 800 square feet of land than it is to buy 4000. But where this gets interesting is that those denser uses may cause higher land prices. Let’s walk through how:

- Say that 4000 sqft lot is zoned to only allow a single-family home. Richie McRicherson is willing to pay $1M so he can build a house on that land. The land sells for 1 MILLION DOLLARS.

- Now, suppose the land is zoned to allow a duplex. 2 households who each have $600k pool their money together and outbid Richie. The land sells for 1.2 MILLION DOLLARS.

- Finally, suppose the land is zoned to allow a 5-unit condo building. 5 households who each have $400k pool their money and outbid both Richie and the duplex buyers. The land sells for 2 MILLION DOLLARS.

| Building | Land Price | Land Price/Sqft | Land Price/Household |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single family home | $1,000,000 | $250 | $1,000,000 |

| Duplex | $1,200,000 | $300 | $600,000 |

| 5-unit condo building | $2,000,000 | $500 | $400,000 |

It is really important to note that even though allowing more homes drove land prices up, households are paying less for land.

OK that’s the theory; what about in practice?

It can be hard to observe this in real life, because dense city centres tend to be pretty expensive. That’s a complicated topic that’s beyond the scope of this blog post, but there are places where it’s easy to see this specific phenomenon in Vancouver with a map of land values. For example:

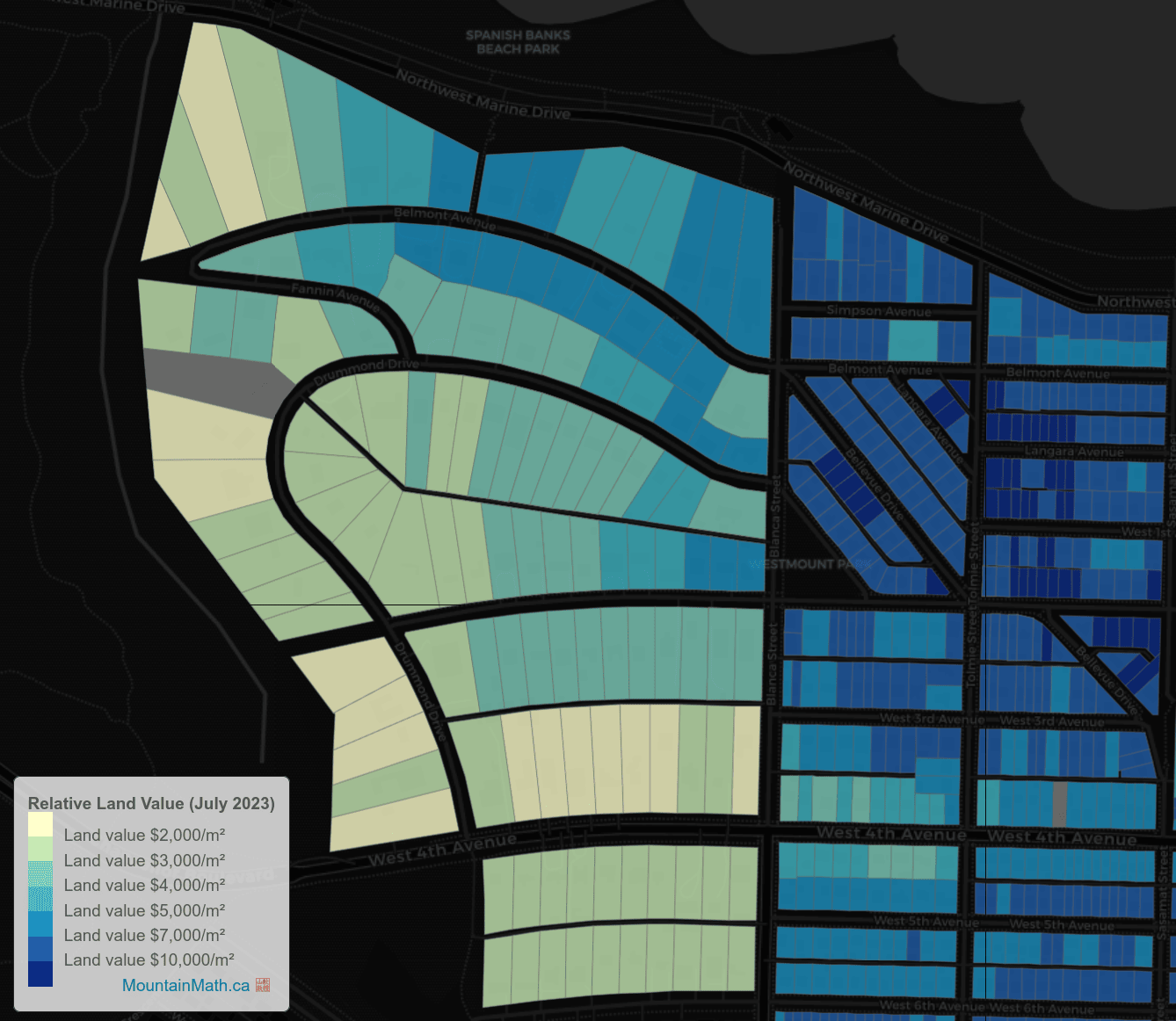

North West Point Grey

This is one of the most expensive neighbourhoods in Vancouver, by design. Apartments are forbidden everywhere, only houses are allowed. And city planning rules require each house to use up much more land west of Blanca Street:

| Area | Minimum Lot Size | Land Price/Sq Ft | Land Price/Lot |

|---|---|---|---|

| West of Blanca | 12,000-18,000 sqft | Usually around $300 | $7M-$30M |

| East of Blanca | 3000-5400 sqft | Usually around $800 | $3M-$8M |

This is exactly what we were talking about. When the city lets people use less land per home, land prices go up and home prices go down. To be clear, $3M still isn’t cheap; we should go a lot further.

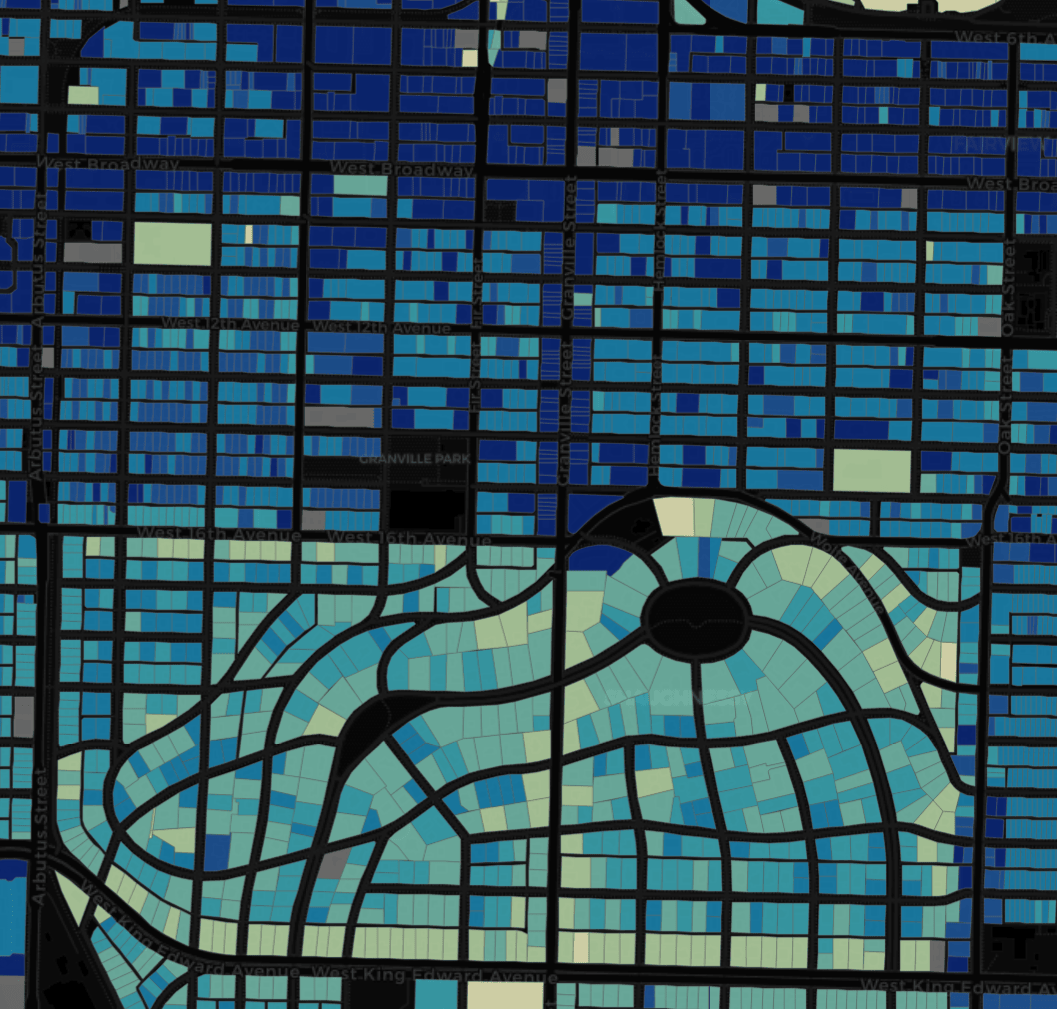

Shaughnessy

It’s a similar story in Shaughnessy, historically Vancouver’s most exclusive neighbourhood:

South of 16th we zone for mansions on very large lots (making the land relatively cheap), and north of 16th we allow apartments and condo buildings (making the land relatively expensive). If you know Vancouver at all, you know that those apartments are a lot cheaper than the $10M+ Shaughnessy mansions!

Takeaway

It’s important to distinguish between the cost of land per square foot and the cost of land per home. Limiting density does work to drive the former down, but at a terrible cost: it stops people of modest means from pooling their resources to outbid someone much richer.